OTITIS EXTERNA

- At a glance

- WHAT DOES IT LOOK LIKE?

- WHAT ELSE LOOKS LIKE THIS?

- HOW DO I DIAGNOSE IT?

- HOW DO I MANAGE IT?

- COMMENTS

AT A GLANCE

- Otitis externa is inflammation of the epithelium that lines the external auditory canal

- Not necessarily a diagnosis for one distinct problem, but often a presentation of clinical signs with multifactorial causes

- Otitis externa was recently number one reason for dog pet claims (VPI pet insurance, 2012)

The causes of otitis externa have been classified into causes (primary and secondary) and factors (predisposing and perpetuating).

- Primary causes: create disease in a normal ear. Once a primary cause alters the aural environment, secondary infections often develop.

Examples: allergy, foreign bodies, parasites, endocrine disease, immune-mediated disease, epithelialization disorders and others - Secondary causes: create disease in an abnormal ear.

Examples: bacteria, yeast, fungal, medication reaction, physical trauma (e.g. Q-tip)

Factors are elements of the disease or pet that contributes to or promote otitis externa, generally by altering the structure, function, or physiology of the ear canal. Factors are classified as:

- Predisposing factors: present prior to the development of ear disease and increase the risk for development of otitis externa.

Examples: conformation (stenotic canals, pendulous pinna), excessive moisture, obstructive ear disease, primary otitis media, and others - Perpetuating factors: occur as a result of otic inflammation and may prevent resolution of otitis externa when treatments are only directed at primary and secondary causes.

Examples: ear canal edema, proliferative changes or altered migration, tympanum rupture, and others

- Often all categories are involved, but each category must be identified and addressed separately.

- In this way a more accurate prognosis can be provided, a specific and safe therapeutic plan formulated, and the best possible outcome from treatment assured.

WHAT DOES IT LOOK LIKE?

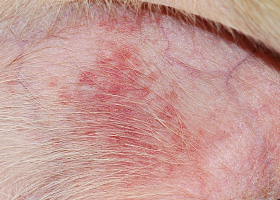

- Pruritus (e.g., head shaking, ear scratching) and malodor = most apparent clinical signs

- Aural redness, discharge, and pain are also common

WHAT ELSE LOOKS LIKE THIS?

- Ears (e.g. affected pinna, aural hematoma, affected skin caudal to the pinna and around the vertical canal)

- Head (e.g. pain when eating, head shyness, pyotraumatic dermatitis of lateral face)

- Neurologic (e.g. head tilt, facial nerve abnormalities, or Horner's syndrome)

HOW DO I DIAGNOSE IT?

- History (otic, dermatologic)

- Physical Examination (otic, dermatologic)

- Ancillary tests such as cytology

Otic history: unilateral or bilateral disease, age of onset, pruritus, seasonality, inflammation vs infection, response to therapy

Dermatologic history: concurrent skin disease, age of onset, pruritus, seasonality, family history, response to therapy

Otic exam:

- gross (unilateral or bilateral, primary or secondary, acute vs chronic, characterization of discharge)

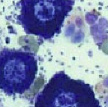

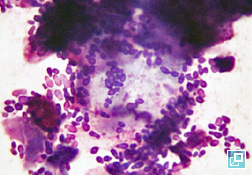

- microscopic/cytologic evaluation of exudate or cerumen obtained from the horizontal ear canal is imperative and can provide immediate diagnostic information.

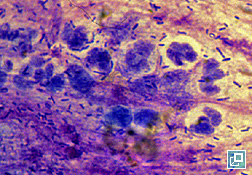

Diagnostic technique: Exudate obtained with a cotton-tipped applicator is rolled onto a glass slide and stained with a 3-step quick stain or modified Wright’s stain, and examined microscopically. Smears should be examined first under low-power magnification and then under high-power (using immersion oil) for numbers and morphology of bacteria, yeasts, and white blood cells; evidence of phagocytosis of microorganisms; fungal hyphae; and acantholytic or neoplastic cells.

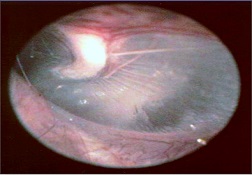

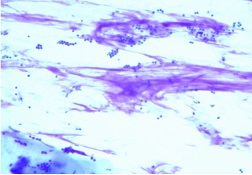

In addition to stained cytology, otic exudate should be examined for eggs, larvae, or adults of the ear mite Otodectes cynotis and other ectoparasites. Smears are made by combining cerumen and otic discharge with a small quantity of mineral oil on a glass slide. A coverglass should be used, and the smear examined under low-power magnification. Rarely, refractory ceruminous otitis externa may be associated with localized proliferation of Demodex sp in the external ear canals of dogs and cats and may be the only area on the body affected. - otoscopic (i.e. changes in ear canal diameter, pathologic changes in the epithelium, quantity and type of exudate, parasites, foreign bodies, neoplasms, and changes in the tympanic membrane)

Dermatologic exam: concurrent skin lesions and history of other skin disease often helps lead to proper primary diagnosis of otitis externa. In one study, concurrent skin lesions were present in 76% of animals with chronic otitis externa.

Ancillary tests:

Culture and susceptibility testing are indicated if otitis media is present or when systemic therapy will be prescribed for severe otitis externa (e.g. cytology reveals large numbers of rods or empirical therapy has been ineffective). Samples for culture should be taken with a sterile culturette from the horizontal canal (the region where most infections arise) or from the middle ear in cases of tympanic rupture and/or otitis media.

Histopathologic changes associated with chronic otitis externa are often nonspecific. Biopsies from chronic, obstructive, unilateral otitis externa may reveal whether neoplastic changes are present. Otherwise, biopsy for histopathology is generally not recommended from the ear canal, however biopsies of pinnal lesions may be helpful in diagnosis of immune-mediated diseases and/or vasculitis.

Imaging (Computed tomography or Magnetic Resonance Imaging ) should be performed for cases of severe, chronic otitis or when proliferative tissues prevent adequate visualization of the tympanic membrane or when otitis media is suspected, and when neurologic signs accompany otitis externa.

HOW DO I MANAGE IT?

- Treatment of otitis externa depends on identifying and controlling, to the extent possible, all the causes and factors involved in the disease

- Client education is critical to achieve good compliance

- Follow-up otoscopic exams and cytology evaluations important to achieving successful outcomes

- Major categories of treatments for otitis externa are listed in the table below.

| MAIN TREATMENT CATEGORIES FOR OTITIS EXTERNA (See Muller and Kirk Reference) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TREATMENT CLASS | ROUTE ADMINISTERED | INDICATION | ||

| Analgesics / Anesthetics |

Systemic

|

|

||

|

Topical

|

|

|||

| Antibiotic |

Topical

|

|

||

|

Systemic

|

|

|||

| Antifungal |

Topical

|

|

||

|

Systemic

|

|

|||

| Antiseptic / Drying agents |

Topical

|

|

||

| Ceruminolytics |

Topical

|

|

||

| Cleansers |

Topical

|

|

||

| Gluccocorticoids |

Topical

|

|

||

|

Systemic

|

|

|||

| Parasiticides |

Topical

|

|

||

|

Systemic

|

|

|||

COMMENTS

- The best treatment approach is to develop a plan that considers each cause or factor and how the response to treatment will be monitored

- Ear cleaning is an essential component of effective management of otitis externa

- Client education on the importance of compliance and the need for a diagnostic work-up in recurrent or non-responsive cases is crucial

- Treatment plans must be feasible for the pet owner in order to achieve compliance and successful treatment outcomes

- Unresolved cases can erode pet owner confidence in their veterinarian's abilities

- Timely referral to a local dermatologist for resistant or recurrent cases is strongly recommended

- A variety of surgical procedures may be appropriate to recommend to owners of fractious animals, when severe proliferative changes and calcification of the ear cartilage is present, and when neoplasia is diagnosed.

References

- Miller W, Griffin C, Campbell K. Muller and Kirk's Small Animal Dermatology, ed 7, Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2013, pp 741-767.

- The Merck Veterinary Manual. Otitis Externa. Available at: http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/index.jsp?cfile=htm/bc/30900.htm&word=otitis%2cexterna. Accessed February 1, 2013.

- Morris DO: Medical therapy of otitis externa and otitis media. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 34(2):541-555,vii-viii, 2004.

- Nuttall T, Carr MN: Topical and systemic antimicrobial therapy for ear infections. In Affolter VK, Hill PB, editors: Advances in Veterinary Dermatology, Ames, 2010, Wiley-Blackwell, pp 402-407.

abscess

A discrete swelling containing purulent material, typically in the subcutis

Perianal abscess in a dog

alopecia

Absence of hair from areas where it is normally present; may be due to folliculitis, abnormal follicle cycling, or self-trauma

Extensive alopecia secondary to cutaneous epitheliotropic lymphoma

alopecia (“moth-eaten”)

well-circumscribed, circular, patchy to coalescing alopecia, often associated with folliculitis

“Moth-eaten” alopecia secondary to superficial bacterial folliculitis

hemorrhagic bullae

Blood-filled elevation of epidermis, >1cm

Interdigital hemorrhagic bulla in a dog with deep pyoderma and furunculosis

comedo

dilated hair follicle filled with keratin, sebum

Comedones on the ventral abdomen of a dog with hypercortisolism

crust

Dried exudate and keratinous debris on skin surface

Multifocal crusts due to pemphigus foliaceus

epidermal collarettes

Circular scale or crust with erythema, associated with folliculitis or ruptured pustules or vesicles

Epidermal collarettes in a dog with Staphylococcus superficial bacterial folliculitis

erosion

Defect in epidermis that does not penetrate basement membrane. Histopathology may be needed to differentiate from ulcer.

Erosions in a dog with vasculitis

erythema

Red appearance of skin due to inflammation, capillary congestion

Erythema in a dog with cutaneous drug eruption

eschar

Thick crust often related to necrosis, trauma, or thermal/chemical burn

Eschar from physical trauma

excoriation

Erosions and/or ulcerations due to self-trauma

Excoriations in a cat with atopic dermatitis

fissure

Excessive stratum corneum, confirmed via histopathology. This term is often used to describe the nasal planum and footpads.

Fissures of the footpads in a dog with superficial necrolytic dermatitis

fistula

Ulcer on skin surface that originates from and is contiguous with tracts extending into deeper, typically subcutaneous tissues

Perianal fistulas in a dog

follicular casts

Accumulation of scale adherent to hair shaft

Follicular casts surrounding hairs from a dog with hypothyroidism

hyperkeratosis

Excessive stratum corneum, confirmed via histopathology. This term is often used to describe the nasal planum and footpads.

Idiopathic hyperkeratosis of the nasal planum (left) and footpads (right)

hyperpigmentation

Increased melanin in skin, often secondary to inflammation

Inflammatory lesions (left) resulting in post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (right)

hypotrichosis

Lack of hair due to genetic factors or defects in embryogenesis.

Congenital hypotrichosis in chocolate Labrador puppies.

lichenification

Thickening of the epidermis, often due to chronic inflammation resulting in exaggerated texture

Lichenification of skin in a dog with chronic atopic dermatitis and Malassezia dermatitis

macule

Flat lesion associated with color change <1cm

Pigmented macule (left) Erythematous macule (right)

melanosis

Increased melanin in skin, may be secondary to inflammation.

Post inflammatory hyperpigmentation of this dog’s thigh

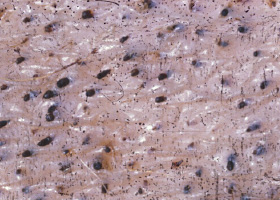

miliary

Multifocal, papular, crusting dermatitis; a descriptive term, not a diagnosis

Miliary dermatitis in a flea allergic cat

morbiliform

A erythematous, macular, papular rash; the erythematous macules are typically 2-10 mm in diameter with coalescence to form larger lesions in some areas

Morbiliform eruptions in a dog with a cutaneous drug reaction

onychodystrophy

Abnormal nail morphology due to nail bed infection, inflammation, or trauma; may include: Onychogryphosis, Onychomadesis, Onychorrhexis, Onychoschizia

Onychodystrophy in dog with chronic allergies

onychogryphosis

Abnormal claw curvature; secondary to nail bed inflammation or trauma

Onychogryphosis in a dog with symmetric lupoid onychodystrophy

onychomadesis

Claw sloughing due to nail bed inflammation or trauma

Onychomadesis in a dog with symmetric lupoid onychodystrophy

onychorrhexis

Claw fragmentation due to nail bed inflammation or trauma

Onychorrhexis in a dog with symmetric lupoid onychodystrophy

onychoschizia

Claw splitting due to nail bed inflammation or trauma

Onychoschizia in a dog with symmetric lupoid onychodystrophy

patch

Flat lesion associated with color change >1cm

Hypopigmented patch (left), erythematous patch (right)

petechiae

Small erythematous or violaceous lesions due to dermal bleeding

Petechiae in a dog with cutaneous vasculitis

phlebectasia

Venous dilation; most commonly associated with hypercortisolism

Phlebectasia and cutaneous atrophy due to hypercortisolism in a dog

plaques

Flat-topped elevation >1cm formed of coalescing papules or dermal infiltration

Plaques in a cat with cutaneous lymphoma

pustule

Raised epidermal infiltration of pus

Pustules on the abdomen of a dog with superficial staphylococcal pyoderma.

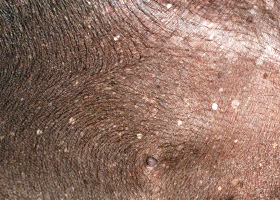

scale

Accumulation of loose fragments of stratum corneum

Loose, large scales due to ichthyosis in a Golden Retriever

scar

Fibrous tissue replacing damaged cutaneous and/or subcutaneous tissues

Scarring (right) following the healing of an ulcer (left) in a dog with sterile nodular dermatitis

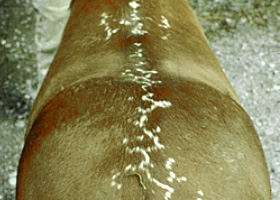

serpiginous

Undulating, serpentine (snake-like) arrangement of lesions

Serpiginous urticarial lesions on a horse

telangiectasia

Permanent enlargement of vessels resulting in a red or violet lesion (rare)

Telangiectasia in a dog with angiomatosis

ulcer

A defect in epidermis that penetrates the basement membrane. Histopathology may be needed to differentiate from an erosion.

Ulcerations of the skin of a dog with vasculitis.

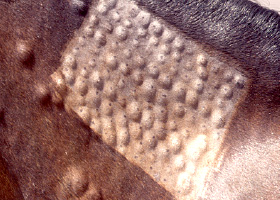

urticaria

Wheals (steep-walled, circumscribed elevation in the skin due to edema ) due to hypersensitivity reaction

Urticaria in a horse

vesicle

Fluid-filled elevation of epidermis, <1cm

Vesicles and bullae on ear pinna due to bullous pemphigoid

wheal

Steep-walled, circumscribed elevation in the skin due to edema

Wheals associated with intradermal allergy testing in a horse